Did you know “Mat” actually means “control” in the language of The Wheel of Time’s Old Tongue?

Leading up to the release of The Wheel of Time Companion on November 3, Tor.com and Harriet McDougal, Alan Romanczuk, and Maria Simons are excerpting portions and entries from its massive store of notes, illustrations, and encyclopedia entries. Unfamiliar with the Companion? Long-time series editor and Robert Jordan’s wife Harriet explains its compilation here and offers a thank you to fans of the series.

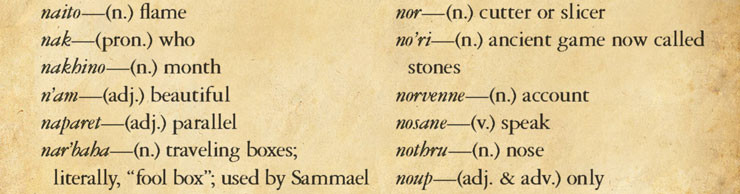

Today, we’re offering a glimpse at the Old Tongue dictionary tucked inside the Companion’s pages: the listings for M, N, and O. The full dictionary itself includes additional sections on popular phrases, pluralization, construction of verbs, how apostrophes work, and more.

Read more excerpts from The Wheel of Time Companion at this link.

M

m—(prefix) means “of”

ma—(prefix) indicates importance

ma—(v.) “you give”

maani—(adv.) very

maast—(adj.) necessary

machin—(n.) destruction

Machin Shin—(n.) “journey of destruction”; the Black Wind, a major threat in the Ways

mad—(adj.) loud

mael—(n.) hope

mafal—(n.) mouth or pass

Mafal Dadaranell—(n.) “pass at the father of mountain ranges”; ancient name for Fal Dara

magami—(n.) little uncle; what Amalisa called King Easar in private

mageen—(n.) daisy

mah’alleinir—(n.) he who soars; literally “seeking man of the stars”; the name Perrin gave to his Power- wrought hammer

mahdi—(n.) seeker; used for leader of Tuatha’an caravan

mahdi’in—(n.) seekers

mahrba—(v.) paint

mai—(n.) maiden(s)

makitai—(n.) wheel

mamai—(n. & adj.) future

mamu—(n.) mother

man—(adj.) related to blade/sword (“man” has the same root as “war,” “violence” or “aggression”)

mandarb—(n.) blade; name of Lan’s stallion

Manetheren—(n.) mountain home; one of the Ten Nations

manetherendrelle—(n.) waters of the mountain home

manive—(v.) drive

manivin—(n.) driving

manshima—(n.) sword/blade

manshimaya—(n.) my own sword

mar—(n.) game

maral—(adj.) destined

marath—(prefi x) indicates that something must be done, suggesting urgency; Seanchan word

marath’damane—(n.) those who must be leashed/one who must be leashed; Seanchan term

marcador—(n.) hammer

marna—(v.) swim

maromi—(v.) crush

mashi—(n. & v.) love

mashiara—(n.) my love; but a hopeless love, perhaps already lost; Lan to Nynaeve

masnad—(n.) trade

maspil—(n.) butter

mastri—(n.) fish

mat—(v.) control

matuet—(adj.) important

ma’vron—(n.) watchers of importance

mawaith—(n.) reaction

medan—(n.) sugar

melaz—(n.) inn

melimo—(n.) apple

mera—(prep.) without; lacking

Mera’din—(n.) the Brotherless; used by Aiel

merwon—(adj.) boiling

mesaana—(n.) teacher of lessons;

name of one of the Forsaken

mestani—(n.) lessons

mestrak—(n.) necessity

m’hael—(n.) leader (capitalized implies “Supreme Leader”; title Taim gave himself)

mi—(poss. pron.) my

mia—(pron.) me; myself

Mia’cova—(n.) One Who Owns Me, My Owner; term used by Moghedien after she was enslaved by a mindtrap

miere—(n.) ocean/waves

mikra—(n.) shame

min—(adj.) little

minyat—(adj.) eight, a quantifier of material objects

minye—(adj.) eight, descriptive of the immaterial, such as ideas, arguments or propositions

miou—(n.) cat

mirhage—(n.) pain, or the promise or expectation of pain

misain—(v.) am (insistent; emphatic)

mist—(n. & adj.) middle

mitris—(adj.) dirty

modan—(n.) approval

moghedien—(n.) a particular breed of spider; small, deadly poisonous and extremely reclusive; name of a Forsaken

mokol—(n.) milk

mon—(adj.) related to scythe

moodi—(adj.) frequent

mora—(n.) the people or a population

morasu—(n.) morning

morat—(n. prefix) handler/controller; i.e., one who handles or controls; used by the Seanchan (as in morat’raken, one who handles raken)

mordero—(adj.) death

moridin—(n.) a grave; tomb; also, the name of a Forsaken, for whom the word’s meaning refers to death

moro—(adv. & conj.) so

mos—(adj., adv. & prep.) down

mosai—(adj.) low

mosiel—(v.) lower

mosiev—(adj.) lowered or downcast

motai—(n.) Aiel name for a sweet crunchy grub found in the Waste

mourets—(n.) mushroom(s)

mozhlit—(adj.) possible

m’taal—(adj.) of stone

muad—(n., adj. & adv.) foot/on foot/afoot

muad’drin—(n.) infantry/footmen

muaghde—(n.) meat

mukhrat—(adj.) private

mund—(adj.) high

mustiel—(n.) sock

mystvo—(n.) office

N

n—(prep. prefi x) means “of” or “from”

nabir—(n.) fire

nachna—(n.) science

nadula—(n.) force

Nae’blis—(n.) title of Shai’tan’s first lieutenant

nag—(n.) day

nagaru—(n.) snake

nahobo—(adj.) full

nahodil—(n.) cushion

nai—(n.) knife, dagger, blade; a blade smaller than a sword’s blade; can be used in modification also to mean “stabbing”

nais—(v.) smell

naito—(n.) flame

nak—(pron.) who

nakhino—(n.) month

n’am—(adj.) beautiful

naparet—(adj.) parallel

nar’baha—(n.) traveling boxes; literally, “fool box”; used by Sammael

nardes—(n.) thought

narfa—(adj.) foolish

nasai—(n., v. & adj.) wrong

nausig—(n.) boat

navyat—(adj.) nine, a quantifier of material objects

navye—(adj.) nine, descriptive of the immaterial, such as ideas, arguments or propositions

nayabo—(n.) prison

n’baid—(adj.) automatic

n’dore—(adj.) of/from the mountains

neb—(n.) mist

nedar—(n.) tusked water pig found in the Drowned Lands

neidu—(adj.) new

neisen—(adv.) why

nemhage—(n.) distribution

nen—(suffix) like adding “er” to an English verb, indicating one who or that which does, or those who cause

nesodhin—(prep.) through; through this; through it

ni—(prep.) for

niende—(adj.) lost

nieya—(v.) step

ninte—(poss. pron.) your (used more formally than “ninto”)

ninto—(poss. pron.) your

nirdayn—(n.) hate

no—(conj.) but

no—(pron.) me

nob—(v.) cut

nodavat—(n.) produce

nolve—(v.) give

nolvae—(v.) is given

nor—(n.) cutter or slicer

no’ri—(n.) ancient game now called stones

norvenne—(n.) account

nosane—(v.) speak

nothru—(n.) nose

noup—(adj. & adv.) only

nupar—(n.) base, as in bottom or support

nush—(adj.) deep

nyala—(n.) country

nye—(adv.) again

Nym—(n.) a construct from the Age of Legends, a being who has beneficial effects on trees and other living things

O

o—(adj.) a

ob—(conj.) or

obaen—(n.) a musical instrument of the Age of Legends

obanda—(n.) door

obidum—(n.) spade

obiyar—(n.) position

obrafad—(n.) view

obram—(n.) impulse

ocarn—(n.) toe

odashi—(n.) weather

odi—(pron. & adj.) some

odik—(n.) secretary

oghri—(n.) sky

ohimat—(n.) comparison

olcam—(n.) tin

olesti—(n.) pants

olghan—(n.) drawer

olivem—(n.) pencil

olma—(n. & adj.) poor

ombrede—(n. & v.) rain

on—(suffix) denotes plural form

onadh—(n.) arch

onguli—(n.) ring

onir—(n.) star(s)

oosquai—(n.) a distilled spirit; used by Aiel

orcel—(n.) pig

ordeith—(n.) wormwood; name taken by Padan Fain among the Whitecloaks

orichu—(n. & v.) plow

orobar—(n.) danger

ortu—(adj.) open

orvieda—(v.) print

osan—(adj.) left-hand or left-side

osan’gar—(n.) left-hand dagger; name of a Forsaken

ospouin—(n.) hospital

ost—(prep.) on

otiel—(n.) sponge

otou—(n. & adj.) top

otyat—(adj.) four, a quantifier of material objects

otye—(adj.) four, descriptive of the immaterial, such as ideas, arguments or propositions

ounadh—(n.) wine

ovage—(n.) window

o’vin—(n.) a promise; agreement

ozela—(n.) goat

This one is much better. It gives an idea of who one of my favorite “late introduction characters” was: Nakomi:

nak: Who

mi—(poss. pron.) my

makitai—(n.) wheel

She is an avatar of the Wheel. Not a new character at all. Gives a new meaning to “The Wheel weaves…”

This is more of what I expected out of the Companion. Good to see.

mesaana—(n.) teacher of lessons;

miou—(n.) cat

Awesome!

I like that Mat’s name meant something in the Old Tongue. I wonder how the name Mat became a name in Two Rivers. I also liked we were told the meaning of Mesaana in the Old Tongue. As an insult, how appropriate. She always wanted to be a researcher but she was denied that position. Once she turned to the Shadow, Mesaana was given an name that included “teacher” in its meaning. I am also glad we will learn what all the other Forsaken names mean.

Thanks for reading my musings.

AndrewHB

Nakomi

Nak – Who

O – a

mi- my

Who Am I.

It fits.

@@.-@: Except his name is Matrim, so it doesn’t actually come from this.

@5, Yehuda, I started to go with that, then I noticed that since there’s no grammar, we don’t really know how the words are combined into names. I noticed makitai and wondered about the possibility. Her actions seem to indicate something other than an elevated human and why not. She is definitely weaving changes in the pattern.

Nolvae that it’s only three consonants given, the grammar is somewhat difficult to deduce. Nolve me more complete examples and I’ll wrinkle out the grammar … but in what context misain ye M’olcam Olesti ob N’olcam Olesti? Is it like Deutsches Grammaphone and Ludwig van Beethoven?

@8, I think we may have enough to at least make a teeny start on some longstanding puzzles about Old Tongue grammar:

1. It has grammar. That’s significant. Creating any degree of invented language, as opposed to just mutually phonetically plausible vocabulary bits, is not necessary to write a fantasy novel, and WoT fans have been arguing for years about whether Old Tongue grammar even exists. But at the very least, we have well-defined parts of speech and an implication, though not the details, of verbal inflection (at least one active/passive verb pair in this list–and isn’t it appropriate to WoT that the first thing we learn about verb grammar is active v. passive constructions?)

2. It is based on roots that include vowels, which places it closer to an Indo-European way of relating words to other words than, say, a Semitic way (consonant bases).

3. As I think you’re picking up, it handles relationships between nouns and other nouns in a very weird way, particularly the “of” relationship. It’s almost certainly not inflected, or if it is inflected it has a very small number of case forms and mostly uses other ways of showing how nouns relate to other nouns, probably word order. But “of” is clearly weird, because on the one hand there is a vocabulary word for “of”, but on the other hand there are, as I think you noticed, lots of two-word phrases that translate to English “X of Y”, but m’ is not used. We haven’t seen enough of other major noun-relation words like “to” or “for” to puzzle out more, but we can conclude. . .this is either poorly thought through, or complex and quite weird. “Of” can have a pretty wide range of meanings–could m’ only cover a small part of the range of English “of”?

4. It uses at least some parts of speech that don’t really exist in English. “Ma” is called a “prefix”, but functionally it sounds a lot more like a particle (part of speech extant in some older Indo-European languages such as Ancient Greek but extinct in English). It’s a word that conveys something closer to what English would do with tone of voice than something you can really translate with an English bit of vocabulary (because if it just meant English “great”, then it would be an adjective).

5. It seems to have some semantic function for the apostrophe, which tends to divide word parts. Is it necessarily a punctuation mark, or is it a “translation-ese” rendering of a glottal stop consonant, like in transliterated Arabic? One thing we really don’t know is whether WoT uses the Roman alphabet. (The world building makes it theoretically possible that it could, but by no means necessary.)

6. As we already knew from the novels, but this is confirmation, the total size of the implied extant vocabulary (as opposed to what’s in the published glossary, i.e. what Jordan actually defined) must be huge. Languages don’t all have the same size dictionaries. This glossary suggests a very large vocabulary with very precise shades of meaning built into individual words (as opposed to the other extreme, which you see for example in Latin, of a very small vocabulary with a gigantic range of potential meanings per word dependent on context).

7. It doesn’t look like it’s meant to be a historical descendant of any First Age (i.e. real) language. Was it in origin an invented language that became a living language in the Age of Legends due to long lifespans and universal education?

@6 Good point. What we don’t know is a) What did Abell think the name Matrim meant when he picked it? and b) If we had the entries for “trim” or “rim”, what would “Matrim” appear to signify in the Old Tongue, even if that isn’t its contemporary meaning? And what would Knotai signify? It’s entirely possible that Mat is, in subtext, dealing with a problem not unlike Rand’s problem in The Great Hunt, where Al’ as a surname prefix has evolved into a patronymic in the Two Rivers but a royal marker in the Borderlands. I’ll be very interested to check the R and T parts of this glossary and see if we can figure out what Tuon thinks “Matrim” means. (Also, could her consistent refusal to call him just “Mat” be an aversion to calling another person something that sounds way too much, to her educated ears, like “Mr. Control”?)

@@@@@9. mutantalbinocrocodile

I deduced from Far Aldazar Din and Far Dareis Mai that far was a possessive use of a dative preposition, used in a manner that is far from usual in English – to the eagle a brother/brothers and to the spear a maiden/maidens. That’s not a totally unusual use of the dative – sometimes you encounter that in Latin and Greek, and it’s often used that way in Hebrew and Arabic. Ie, “unto us a son is born, unto us a son is given“, but equally “to me a son” = “I have a son“.

The problem I see with the Old Tongue is that Robert Jordan never took the time to properly sort out the contradictions. There are parts where it looks like Japanese, then there are parts where it looks like Hebrew or Arabic, then there are parts where it looks like Latin or another Indo-European language.

I’m wondering if he learned some parts of the Montagnard languages of Vietnam? That could account for some more unusual constructions.

Yes, I can definitely see far as dative of possession. But that still leaves the “possession” type relationship in phrases like Machin Shin (which looks like a Hebrew contract form) as opposed to whatever sense of “of” m’ and n’ cover.

Very interesting comment on Montagnard languages. I do think we’ll have to wait to fully resolve this game until we have more than three letters’ worth, because there’s three possible interpretations, the way I’m seeing it:

1) The grammar does not attempt to be consistent. Entirely possible. Again, I don’t in any way EXPECT fictional linguistics to be functional as some kind of genre police demand (see my comments on the Rothfuss thread about what I’m sure are instances of Rothfuss hilariously subverting the invented language trope and getting the fans all worked up trying to puzzle out what are just jokes).

2) It’s intentionally inconsistent, possibly according to geography. There are some consistent geographic pronunciation variants in the phonetic entries of the various novel glossaries, so leaving grammatical variants there on purpose to enhance verisimilitude of such a large continent having only one language might be in line with that style.

3) It’s representing a creole of major First Age languages (re: your Montagnard comment).

Option 1 is still very much live (basically, “This sounds internally consistent, and cool, and not like anyone else’s published phonology”). But I’m just a little suspicious about the thematic precision of these entries suggesting that active/passive voice is the most salient characteristic of a verb (no tense markers, but an active/passive pair in the same tense, and an implication that verb person stops mattering in the passive? That’s a little too thematically relevant to be dismissed as definitely accidental).

Fun game! Good to have a partner!

When I said the Old Tongue doesn’t have a grammar, I meant as in a published grammar as in a Latin grammar for example. Not that there was no grammar to the Old Tongue.

@11 With reference to far as a preposition, I’m thinking–do we ever see it outside Aiel idiom? If not, then that could be evidence for #2 (regional variation).

What does Far Madding mean?

If only I could Compulse someone into making a font out of the alphabet posted in the graphic novel for New Spring and posting it on Dafont.com. My hand is going to be cramping after practicing all these words.

I was excluding Far Madding from consideration because it’s so transparently an English allusion (Thomas Hardy, Far from the Madding Crowd). If bits of comprehensible English are off limits (The Two Rivers, Whitebridge, Eagle-Eye, Farstrider, etc.), then I’d argue that names made from English word parts are too. They seem to belong in the category of “Whatever all the characters are speaking that rationally is a descendant of the Old Tongue but is written in English because of genre conventions”.

@10 I took Knotai to be a pun on “Not I”

@12 Mind posting a link to this Rothfuss thread? Can’t say I have much knowledge of linguistics, but I always appreciate subtle humor (if indeed it’s that).

I was curious as to what Oliver said before stabbing the darkfriend. I can’t find a text for it since I’m listening on audible.